Artist Statement, 2008

It all started when I decided on the spur of the moment to purchase an old postal sorting cabinet on eBay. After getting it home and installed in the living room, I had to figure out what to do with it, so being photographically inclined I thought, 'why not sort snapshots in it?' As a photographer and the keeper of my family's photographs I figured I'd fill all 63 slots; I filled less than a quarter.

So I sorted through all of my photo boxes, eager to fill more slots, and I came upon a stack of Type 669 Polaroid 3½ x 4¼ prints, ones I'd quickly made about twenty years ago using one of those old Vivitar instant slide printers. There were soft-focus images processed using an obscure, highly toxic direct-positive formula I concocted from the Photographer's Formulary (and of which, at the time, I was extremely proud, being the non-technician that I was). Most I had shot using Polaroid 35mm instant slide film--Polagraph, Polapan, and Polablue--gorgeous, silvery slips that, of course, you just couldn't see easily unless you printed them. These were only ever intended for my reference, so I didn't take any particular care with them; besides, I was plagued, it seemed, by technical misfortune: Polaroid slide film had to be processed using a small machine in which you'd roll the film out along with its developing pack, wait a designated number of seconds, then roll it back into the canister.

Many of my rolls were inexplicably streaked in this processing, hence the frequent white stripes that appear in the subsequent prints. As usual, I made the most of these technical mistakes, sometimes more successfully than others, but I had so many of them I couldn't abandon all of the images that had streaking, scratches, or other ailments. And of course, now that all of those products and the equipment are no longer available/obsolete, the materiality of these small prints takes on an added significance.

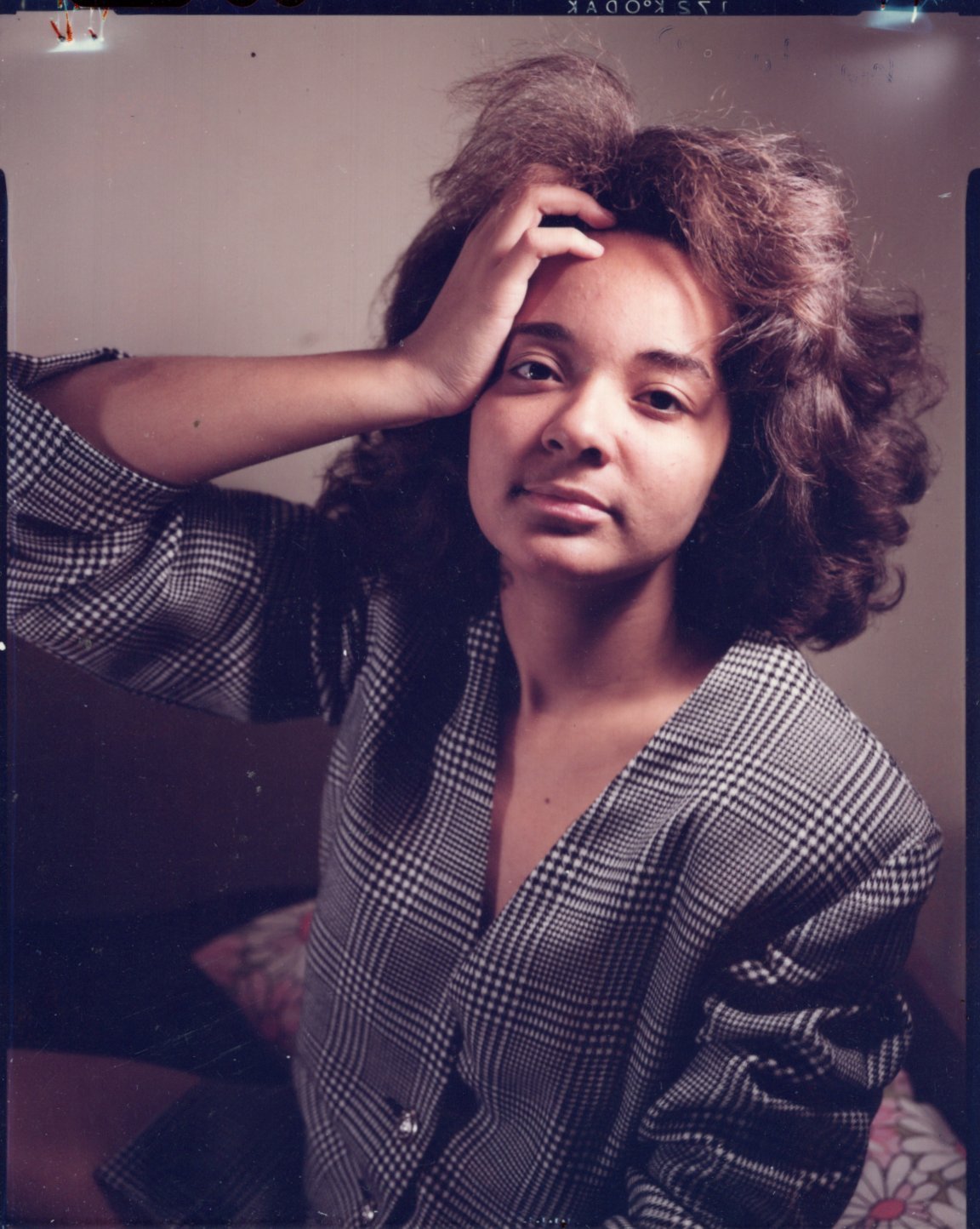

When I began to sort through the stack a funny thing happened-I rediscovered how much I loved these photos, and I loved this fearless young woman who was making them. Here I could see the origins of everything, when photography was endlessly fun and exciting and something I did persistently and constantly in part for the joy of looking. What I saw was a very young photographer enthralled by the medium and its history. There's my homage to my favorite Lee Friedlander self-portrait (Philadelphia, l965), which has always best summed up the utterly mundane and unpretty process of photographing one’s self; my paper backdrop cuttings a la Francis Bruguière--in short, the whole of my photo history education to that point was reflected in the kinds of images I made and sought to make. I loved the camera, but moreover, I trusted it like a confidante; as I wrote then:

... it is as though I can tell it everything

all of my secrets

and it listens, intently, carefully

and repeats it aloud

and I hear it repeated and although it sounds nothing like my original words

I recognize these words…and the camera is right…

There is the image you present to the camera but it is never the one the camera records

the relationship is rather like telling one's deepest secrets to a friend

Making self-portraits and using instant film and prints, I knew I had complete control over the images and thus invested in them a degree of freedom that I might not have if I had thought anyone would ever see them, because I didn't think anyone ever would. They still delight me in their innocence and wonder, with the recognition of my intent now seasoned by my learned ability to gauge whether or not I was successful. Most of these images were never used for any purpose; a number of them were projected to make combination images that were the basis of my best-forgotten Master of Arts exhibition, and some I used in a short video piece Mother and Daughter (2000). And yet looking at them afresh the timing seemed right to bring them out and publish them.

By and large this is the entire stack* as I rediscovered them, save for a few reversed duplicates I'd made playing around with the printing. The slide printer did not render the entire frame, so every image is slightly cropped from the original. They were taken during my late undergraduate and early graduate years of study, when I was roughly between the ages of eighteen and twenty-four. Although I can identify them generally by the setting, I couldn't say for certain when any were taken. I believed there was no audience for them then-I was an unlikely artist who disliked sharing my photographs, in part because they were always pictures of a mostly naked me-and they were perhaps too close to my actual self. The twenty or so intervening years has given them both a necessary distance from the moment in which they were made and an enriched context in which to exist. And then there's the content. What was I thinking, a young Black woman in the mid- 1980s, when I could think of no Black woman's likeness equivalent to the one I was trying to make? I certainly had no artistic precedent, though I had grown up with Black Playboy centerfolds like Jean Bell, Jennifer Jackson, and Julie Woodson framed in our parents' rumpus room (perhaps this was why I it felt somehow like a personal milestone to find out many years later that one of my favorite Black actresses from the '70s, Paula Kelly, was the first woman to show pubic hair in Playboy in August 1969). Though my images would never reveal it I, like many young women, was also heavily influenced early on by the beauty industry and fashion photography; I have a whole series of images for which the backdrop-a corner of my studio--is made up of pages torn from fashion magazines. I probably also would have seen images such as Bruce Davidson's bleak portraits from East 100th Street (1970). These would have been the only celebratory images I'd seen until I discovered Jean Paul Goude's Jungle Fever (1980) while working in the art library in college. The only other nude Black women I would have encountered would have been in the National Geographic magazines-per the old Richard Pryor joke, "the Black man's Playboy"-that we cut up for school reports, or in the actual Playboy and Penthouse issues my father kept under the bathroom sink.

In her 2003 novel A Love Noire, Erica Simone Turnipseed revealed through a conversation between the main character Noire, "a hip, Afro-wearing Ph.D. student," and her date just what even artsy /boho Ivy League-educated Black women (ostensibly like me) thought of the kinds of images I made:

She revealed to him her freshman year at Amherst that was anchored by her cosmopolitan attitude, short-lived half-a-pack smoking habit, and vintage camera that hung around her neck like jewelry.

"You sound like quite the artiste."

"Tell that to my first-year photography professor. She hated my stuff…About two months into the class I just burst out, 'I like to photograph black people, and the black people I know don't let you take pictures of their crotch and their grandmothers' naked breasts like some white people will. Just because every picture I take isn't homoerotic or borderline pornographic doesn't mean it's not art!"' (38)

When I read that brief, almost hostile passage, it stung as though she were wagging a finger directly at me and the images I'd made, because I just don't see the work that way. Playboy-caliber photographs were never my goal; though I knew these images were salacious I never thought of them as porn. They all influenced me, consciously or no; though I never aspired to be them I was certainly inspired by what I perceived as their fearlessness and fierceness, these women who weren't ashamed of their bodies and, in fact, seemed to revel in them. I wanted, in my photographs, to be like them.

In Isabel Coixet's film Elegy (2008), Consuela seeks out her former lover, David, after a two-year separation to ask him to photograph her body before she undergoes a double mastectomy. David, a collector of Edward Weston nudes and peppers, complies. "No one else has looked at my body as beautiful the way you do," she tells him sadly and hopefully, and he obliges as she reclines awkwardly on his sofa and slowly pulls away her cover. She wants the photographs to prove her beauty in that moment; she needs David to validate his desire for her.

My self-portraits were also informed by the history of portraits made by male photographers like Weston of their wives, lovers, and muses. I admired the beauty, simplicity, ond intimacy in those photographs, and I didn't think it was necessary or practical to wait for someone else to want to make them of me. With the self-portrait I could photograph exactly what I was feeling and decide later whether or not to display them. I wanted to know that I could make those kinds of private images myself.

I recognize in these photographs an exploration of one's physicality, beauty, sexuality, power, and pleasure through humor, seduction, and performance. As much as my older, wiser self would like to claim otherwise, what I know is that there was nothing deliberate or political in their creation-that came later-I was a young Black woman exploring the way I looked before the camera. Their directness and honesty and playfulness were only possible for me before I knew the degree to which any of it "mattered." As I continue to see some of my favorite young Black women artists like Takara Portis and Zanele Muholi exploring the representation of our bodies I am certain that it is still important, still vital to make ourselves-our bodies-seen. Several years ago during a Q&A following my lecture on the history of the Black female body in photography, photographer Myra Greene asked about the possibility of "pleasure" for the Black subjects in the photographic process. Though I had not conceptualized my research to that point to include this rather obvious yet complex notion, I haven't been able to stop thinking about it since. I was also inspired by Deborah Willis' project "Posing Beauty," to which I have contributed. In our conversations and elsewhere the words "pleasure" and"beauty" were especially resonant for different reasons, and being privy to the ways in which she was conceptualizing her project also helped me look anew at these images.

It is from the wonderful group of photography instructors I had during this period that I learned to love and understand photography: Susan Jahoda, Virginia Beahan, Emmet Gowin, Tom Barrow, Rod Lazorik, and Patrick Nagatani, and historians Peter Bunnell and Nia Parry. Thomas Allen Harris provided the first encouragement at exactly the right moment; Tate Shaw seconded that enthusiasm and gave it purpose.

*This statement was written in conjunction with the exhibition “Pleasure and Beauty” at Visual Studies Workshop in 2009.